Hot Topic: Energy Management

(published in RFP Magazine, Issue 36 – Nov 2007)

At the very least, corporate real estate executives and facility managers should know of the existence of degree day data, and make an effort to understand its use. Robert Allender, Managing Director, Energy Resources Management, explains why.

The corporate real estate executive (CRE) who is involved in negotiating leases, writing occupied space specifications or guidelines, looking at current and future sustainability and greenhouse gas commitments, or simply hunting around for ways to save his or her company money will find an understanding degree day data is very helpful indeed. A facility manager (FM) arguably has an even more pressing need to incorporate degree day data into his or her daily work. To sell professional services to building owners without integrating best-practice energy management techniques is a risky strategy. Providing input on energy efficiency as part of that work without considering changes in degree days would be equally so.

Degree days are nothing more than the mean of a day’s high and low temperatures adjusted by a certain specified temperature. High plus low divided by two, minus a baseline temperature. Yet every day of the year, all around the world, millions of dollars change hands on the strength of this simple metric. On the Chicago Mercantile Exchange and similar bourses, million-dollar futures contracts are traded daily on behalf of companies that need to hedge against the impact of future hot or cold weather – insurance companies, airlines, oil companies, and agribusinesses – positions often separated by nothing more than a few degree days.

Just as regularly, engineers designing new high-rise buildings make million dollar recommendations to their clients based on calculations similarly incorporating the humble degree day – recommendations about what size chillers to install, how much insulation to specify, and what quality of windows is cost-justifiable. Choices that will go on affecting the profitability of that building for its entire life.

For CREs and FMs, degree day data can also be the key to million dollar decisions. Yet here in Asia only a small portion of CREs and FMs currently make use of this metric (directly, or by instruction to those reporting to them) to give themselves and their companies a competitive advantage. The use this minority of CREs and FMs make of degree day data is for gauging energy efficiency. And the advantage they gain from its use is from making sound decisions, based on fact, rather than by simply guessing. Or from actually making some decision rather than remaining ignorant that there is a decision to be made. In other words the advantage comes from managing energy better.

The climate for change

Now that climate change and sustainability are firmly part of every CRE’s and FM’s responsibilities, the ability to more accurately and professionally manage energy use has become even more of an imperative. And in the next few years, as corporations’ carbon footprints become ever more closely scrutinised, the ability to fully understand and manage energy consumption data is unquestionably going to become a requisite skill.

Degree days are an important concept in the practice of energy management. Both cooling degree days and heating degrees days can be calculated. Cooling degree days indicate some level of cooling is required. Heating degree days denote that heating would be needed to bring the building or space to a comfortable temperature.

Degree days are an important concept in the practice of energy management. Both cooling degree days and heating degrees days can be calculated. Cooling degree days indicate some level of cooling is required. Heating degree days denote that heating would be needed to bring the building or space to a comfortable temperature.

The simple reason that the degree day is an important concept in the practice of energy management is because it allows changes in weather to be factored in when appropriately evaluating energy consumption, alongside other dynamics that will be considered (primarily quantity of space occupied, but perhaps also number of staff, volume of business, and units of production throughput).

Energy management

The ways that degree day data can help CREs and FMs with decision making fall into two categories: comparisons and changes. Degree day data is instrumental in making comparisons between one time period and another, or one facility and another. Comparison with previous periods – this week with last week, this September with last September – will yield significantly more valuable conclusions when the data is normalised for degree day differences.

Likewise, a comparison of one facility – office, shop or whole building – with another, or better yet, with a whole portfolio of the company’s spaces, provides information that is significantly more actionable if the relevant data has been similarly normalised.

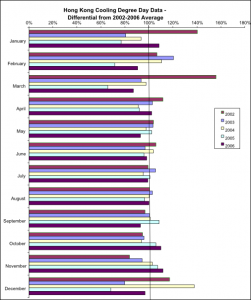

As the graph above shows, Hong Kong’s cooling degree days for any particular month over the past five years could vary wildly from the average of that month. Evaluations related to energy consumption made without considering the true picture would have resulted in some questionable decisions.

Under the heading “Changes”, the second group of decisions enhanced by degree day data includes differences both intentional and unintentional. If your firm has adopted Six Sigma, you will already be familiar with the cusum (cumulative sum) control chart. Cusum is particularly useful in detecting small changes. This technique, in combination with degree day data, can assist decision makers to both detect and quantify changes in energy consumption.

You may want to detect changes due to problems such as operating mistakes, equipment malfunction, or controls flaws, for example. You may also want to detect changes due to the implementation of energy saving measures, new practices or new equipment, for example. Normalising for degree day differences is critical both for estimating the savings that will be enjoyed from implementing those measures, and for calculating the savings that have actually occurred.

Similarly, this data can be used to predict future energy consumption, and therefore provide a target against which actual performance can be measured. Degree days are by no means a perfect way to judge energy efficiency. They do not account for humidity, which makes up a large portion of the thermal load of a building. And they don’t account for many other factors which can affect how much energy a building uses over the same period that is being examined from a degree day perspective. However the ease with which degree days can be calculated, and their own accuracy and repeatability as a metric continue to hold them in first place as the choice of most energy managers, and the senior executives they report to.

Base Temperature

Base temperature, also known as balance temperature, is that point at which neither heating nor cooling is required. There are two meanings of this term that you will come across.

Firstly, references to degree days need to specify to which base the degree days were calculated. Just as temperature scales begin with a nominal value for zero (zero degrees Celsius is the temperature at which water freezes, zero degrees Fahrenheit is the temperature at which an equal weight of water and salt freezes, and zero degrees Absolut is the temperature at which a certain brand of vodka freezes), degree days begin with a nominal value, too. Unfortunately there is no such accepted base for degree days as there is with temperature, so it is necessary to state the base each time. In Britain the common base is 15.5 degrees Celsius, while in the United States a figure of 65 degrees Fahrenheit (roughly 18.3 degrees Celsius) is commonly used.

Secondly, individual buildings have a base temperature, or balance temperature, at which neither heating nor cooling is required. Each has its own base temperature, and a correction factor is available to allow you to adjust nominal degree days so you can compare your building’s operating energy efficiency with other buildings. Of course you are still free to bemoan the constructed energy efficiency you have been burdened with; the base temperature is largely determined by the thermal weight of the building – how proportional its energy usage is to changes in the outdoor temperature. If your building is tightly constructed and well insulated, there will be a higher outdoor temperature at which you need to start adding cooling, and vice versa. This concept has important implications when calculating the expected payback of certain energy saving measures.

On the other hand, equally valuable techniques such as CUSUM do not require adjustment of base temperature, and will reveal changes in consumption – both trends and one-off anomalies – using any scale.